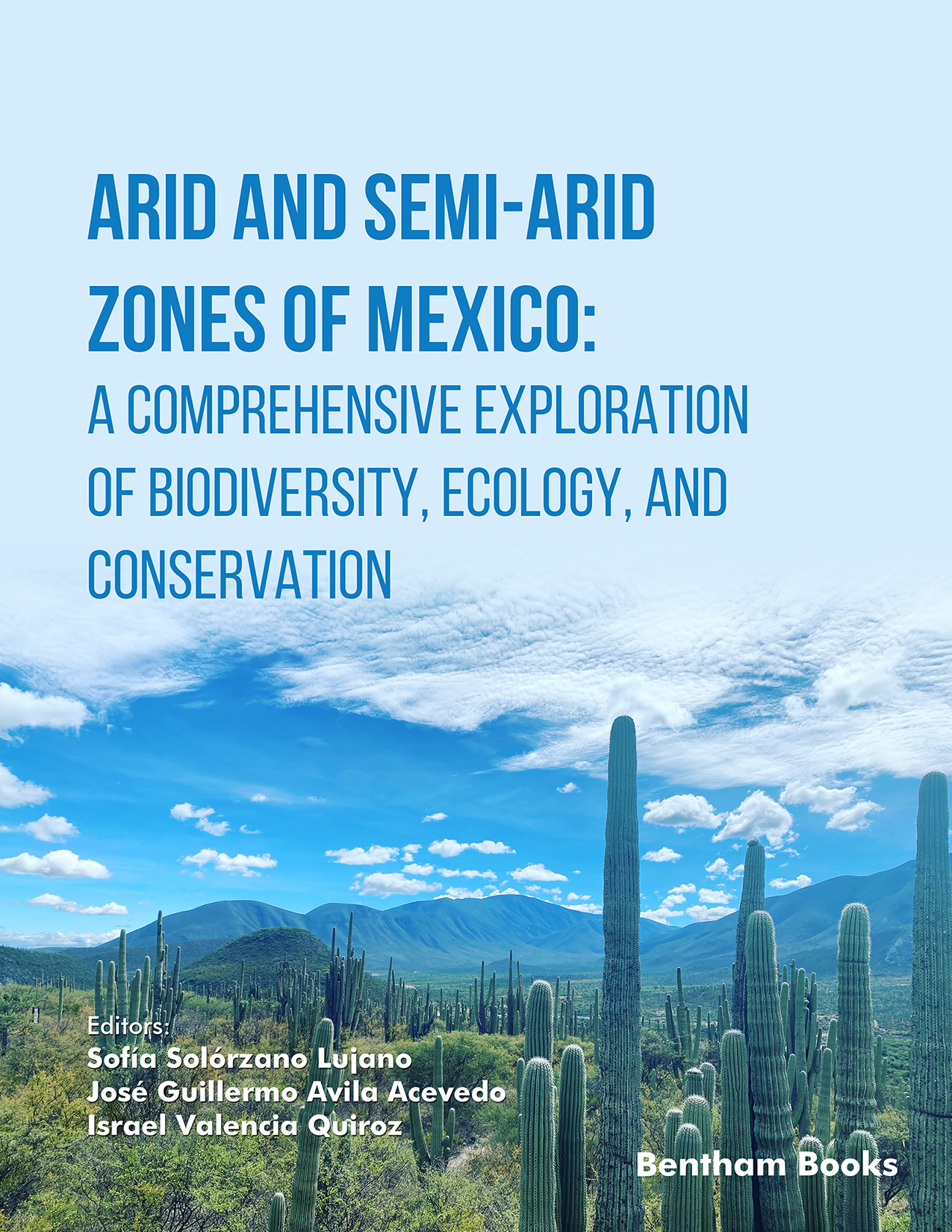

This book is an introduction to the arid and semiarid zones of Mexico, their biological and cultural diversity, and the problems that threaten their conservation. The authors, all scientists from different academic institutions in Mexico had the challenge of writing chapters on a huge area comprising almost half of the country’s territory, covered by these ecosystems. The areas within the polygon defined by arid and semiarid regions were organized along a climatic gradient of increasing aridity from central to northern Mexico. In the central region, the Mexican Altiplano, which is part of the Chihuahuan Desert, is an extensive strip that reaches the southern U.S. border in Texas and includes the states of Chihuahua, Coahuila, Durango, San Luis de Potosí, Sonora and Zacatecas.

Also in central Mexico, the Tehuacán-Cuicatlán Valley region, the southernmost arid zone in Mexico, in the states of Puebla and Oaxaca, is outstanding. It is a region surrounded by complex mountain ranges that form an extraordinarily heterogeneous landscape that harbours great biological and cultural diversity. Attached to the continental territory, it is highly relevant to the arid region of the peninsula of Baja California. In total, the arid and semiarid zones studied in this book include 18 of the 32 states that constitute Mexico.

Although arid environments are generally considered hostile, because of the high temperatures and scarcity of water that characterize them, human communities have found food, medicines, resources for shelter, and clothing in these regions and have occupied them since prehistory. Several studies have recorded nearly 8,000 plant species used by Mexican human cultures throughout the country, about 3,000 of which are from arid and semiarid areas. The interactions with other groups of organisms, including vertebrates and invertebrates are also outstanding. Some chapters of the book illustrate this situation. One of them, for example, compiles information on more than 300 species of medicinal plants from arid environments. In addition, in the arid zones of Sonora, several species of Euphorbia have been identified that contain eugenol, which is effective against microbial biofilms and has high medical potential in combination with antibiotics. Also of note are the diverse species of prickly pear cactus of the genus Opuntia, which have provided edible cladodes and fruits, together with hose produced by the giant columnar cacti such as cardon and saguaro, which have also been basic sources of material for the construction of houses and fences.

The cactus family is the most emblematic plant group of the arid zones of the Americas, and it finds the main centre of diversification in Mexico. Nearly 1520 species of Cactaceae have been recorded worldwide, all of them in the Americas, with the only exception of Rhipsalis baccifera that also occurs naturally in eastern tropical Africa and Madagascar. Almost half of this diversity (850 species) occurs in Mexico and 500 species are endemic to this country. One of the chapters characterizes the distribution of cacti in Mexico and finds that almost 80% of the species are found in arid zones. But this diversity is threatened, as discussed in another chapter of the book, which analysed the Mexican system of natural protected areas and found that the highest proportion of arid and semiarid zones are outside the system and any form of protection.

Not only cacti are important, they are also representative of rich and complex ecosystems, interacting with numerous species of plants, animals, fungi, and microorganisms. Some chapters are dedicated to documenting part of this diversity. One of them analyses groups of invertebrates that play a key role in maintaining ecosystems. Ants, for example, play a crucial role in the flow of matter and energy occurring in arid ecosystems, but the authors estimate that only half of the species living in these areas in Mexico have been described. Similarly, complex assemblages of birds and mammals live in these areas and carry out crucial interactions for the overall maintenance of ecosystems. The study of the diversity of species and especially the diversity of their interactions is of great importance for the design of strategies to conserve the biodiversity of these areas.

Conservation strategies require agreements and participation of the people living in the areas. Social participation is another issue addressed in the book. The use of land and natural resources has had a long history, but especially in the last century, it has been problematic, as large areas have been included in government plans of agroindustrial transformation, cattle ranching, mining, urban expansion, and other destructive activities. These processes are illustrated by the case of the Comarca Lagunera region, in Durango and Coahuila, northern Mexico, where contamination and degradation of soils result from a combination of factors related to human activities. Protecting and restoring the drylands of Mexico require planning, participation, and effective public policies to regulate human actions. Ex-situ conservation of germplasm has been considered a complementary strategy to ensure conservation, especially of plant species. A relevant chapter of this book is dedicated to sharing the inventory of species of arid zones with the readers, which are represented in the Collection Banco de Semillas of the FES Iztacala, UNAM.

This book is an important contribution for all readers interested in the conservation of biocultural diversity in general, and especially for those concerned about the future of the arid and semiarid lands of Mexico and the world.

Alejandro Casas Fernández

Laboratory of Evolution and Management of Genetic Resources

Institute of Research in Ecosystems and Sustainability

National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM)

campus Morelia. Antigua Carretera a Pátzcuaro

No. 8701, Col. Ex-Hacienda de San José de La Huerta 58190

Mexico